On a hot Saturday afternoon in mid-July, hundreds of tattooed young people are gathering in St. Stephen and the Incarnation church in Columbia Heights. They’re here to support local zine-making, an alternative means of publishing that’s like pre-Internet blogging. But instead of posting their points of view on Tumblr, they run them off on a Xerox machine.

“DC Zinefest is the best day of the year,” says JC Parker, 31, a Zinefest organizer, librarian, and “zinester” who writes about the intersections of mental and physical illness. She’s sitting behind a table adorned with many of her zines, including one about what it’s like having juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. She just finished one yesterday about her upcoming hand surgery. Inside, it has black and white photos and X-rays of her contorted hands. “It’s a way for me to process my anxiety about it,” she says.

Behind Parker sits Jaelin Jones, an 18-year-old zine maker who spoke on a people of color panel earlier in the day. “I can be an artist, and I can be brown, and I can talk about what’s important to me,” she says. “I value that.” Today, she’s selling a zine called “Plant Parenthood,” a DIY guide on taking care of plants.

Despite the fact that Parker and Jones could easily publish and share their writings online, they make zines to take part in a living, breathing community. This community is on full display at St. Stephen’s, which has strong historical ties to the DIY punk scene that DC’s known for. Almost 20 years ago, the legendary DC band Fugazi played many times at the church, where guitarist Ian MacKaye‘s father was a member, and it continues to be a gathering place for local punks.

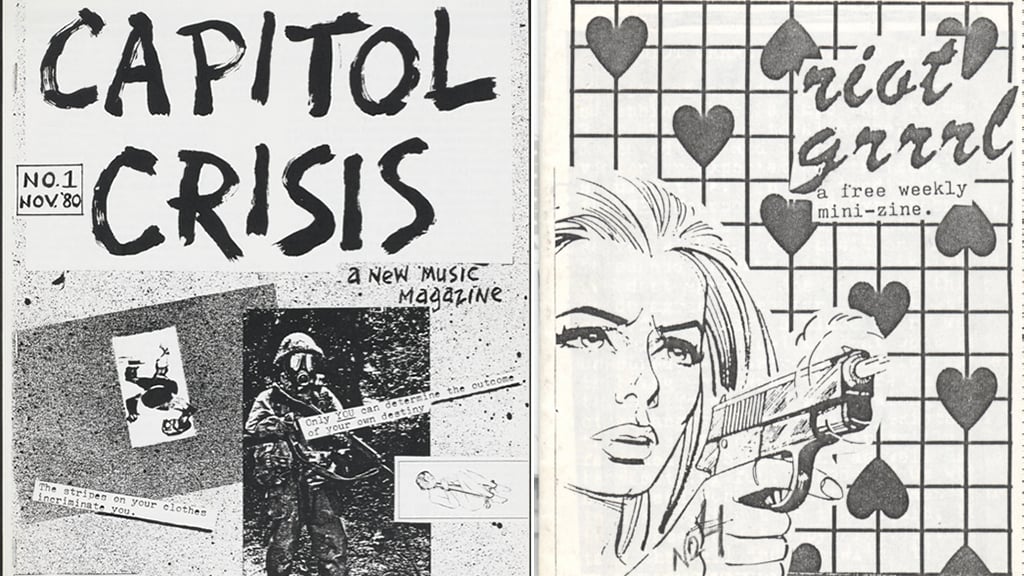

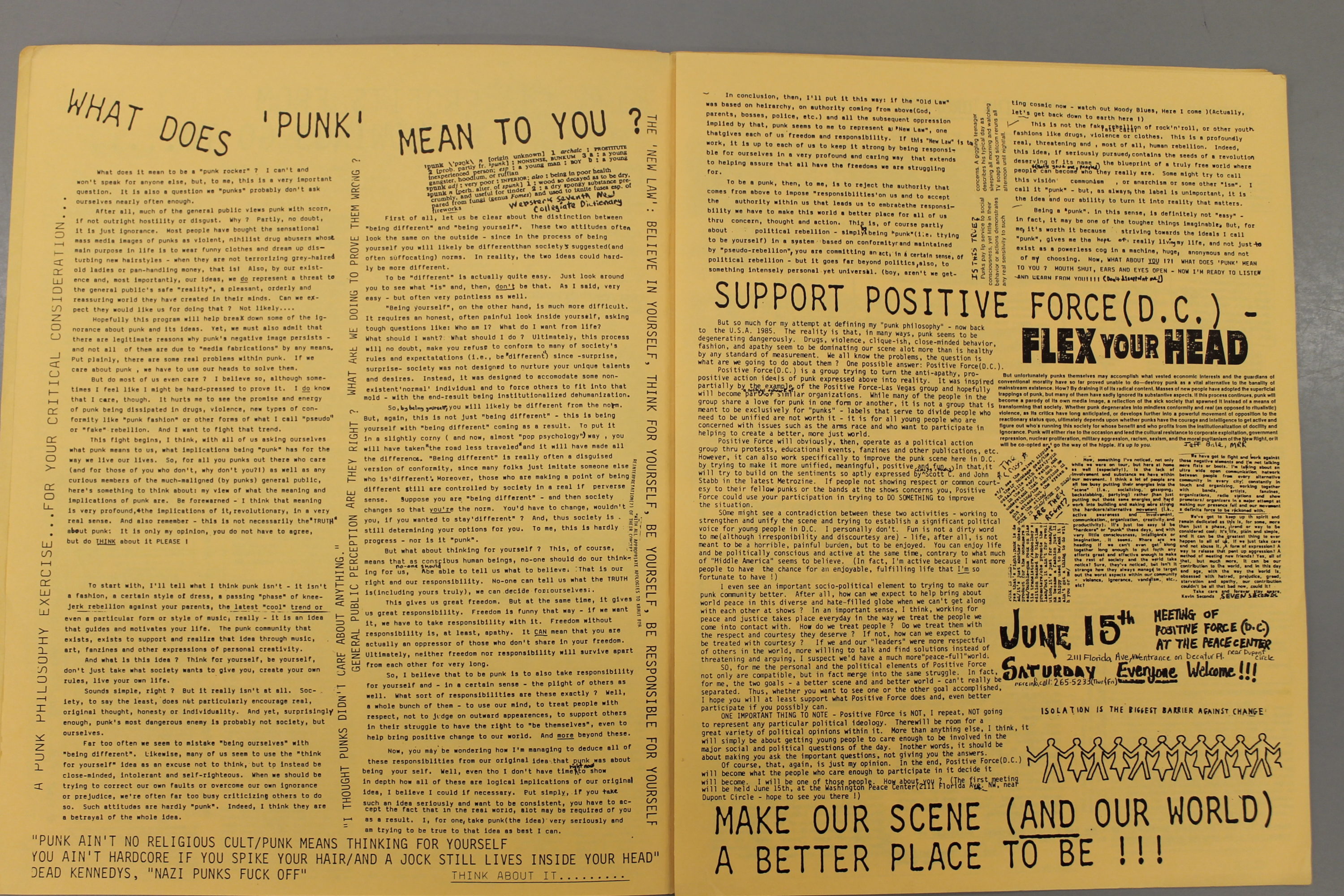

Whether or not the zinesters at Zinefest realize it, they are, in some sense, carrying on the legacy the local punk scene. Starting in the late 1970s, local zines were an imperative tool for spreading the word about bands and communicating their political messages. Later, in the 1990s, zines helped get the feminist Riot Grrrl movement—which started in DC—off the ground. Even the term “Riot Grrrl” comes from a zine of the same name.

Zines are also artifacts of the era. The DC Public Library collects zines and other memorabilia for its DC Punk Archive, created in 2014 to help preserve the scene’s history. The University of Maryland also has a substantial zine collection. “From a historian’s perspective, they are precious documents,” says Mark Andersen, a social activist within the 1980s DC punk scene and one of the main contributors to the Punk Archive. “They are a time capsule from within the community itself.”

Indeed, DC was not the first or only city to harness the power of zines (cities like New York, San Francisco, and London were already doing it). But there’s something about the evolution of zine culture here that’s unique. It directly reflects the do-it-yourself spirit of the tightly knit DC music community, which functioned in opposition to the power structures of the federal government.

And although the music of Fugazi, Minor Threat, and other hugely influential bands are pillars of DC punk history, those pillars were fortified by the creation of zines and the fans who made them. Zines were the connective tissue within the DC scene and a beacon to those outside of it.

***

In order to understand the birth of zines in DC, you have to first understand the roots of local punk. Starting around 1976, garage rock bands such as the Slickee Boys pushed the music scene from stale ’70s rock into a new, fresher direction, setting the stage for the punk bands to experiment in the early ’80s.

Howard Wuefling, who played bass in the Slickee Boys, moved from Pennsylvania to DC in 1974 to start a career in music writing. At the that time, the only non-mainstream publications in the area were alternative newspapers like the Unicorn Times, which covered the underground music scene and some politics.

During a visit to New York City in 1976, Wuefling picked up a copy of New York Rocker, a slick fanzine where musicians wrote about other musicians (The Ramones, Talking Heads, and Patti Smith were featured in the first issue). It inspired him to adapt the idea for the DC music scene. He named it DeScenes (“I have a love for bad puns,” he says). Record stores in DC and in the suburbs sold it for 25 cents.

Capitol Crisis was another late-1970s music zine made by musician and DJ Xyra Harper. “It had that title because [DC] was such a dead town,” Harper says. “Rock clubs were closing, there were very few places for bands to play—people felt stifled by bureaucracy. People were bursting to get out and be creative, and they had to create something because there wasn’t anything.”

Wuefling agrees. He says that in those early days, they were just trying to build a basic infrastructure for the music scene. As physical manifestations of the scene, zines helped build it.

Starting around 1980, DeScenes evolved into DisCords, which included “scene reports” from other cities. Punk kids would send letters into DisCords describing the state of punk in their hometowns. Wuefling says it became a way for music geeks around the country to exchange ideas and take part in a larger community. In that sense, it was the pre-Internet.

DisCords and other early zines were also incubators for writers and musicians who would go on to have big careers. Mark Jenkins, who now writes about music for The Washington Post, NPR, and Slate, was DisCord’s art director and one of the contributors. Ian MacKaye wrote about and interviewed bands like Black Flag, an LA-based hardcore band (MacKaye’s friend Henry Garfield, later Henry Rollins, became Black Flag’s singer in 1981). At the same time, MacKaye’s band the Teen Idles was breaking up, and shortly after he and Jeff Nelson formed Dischord Records and the band Minor Threat.

Minor Threat became known for the “straight edge” philosophy of refraining from drugs and alcohol. The band coined the term with its 1981 song “Straight Edge,” and the idea caught fire within the hardcore community. Hardcore zines with names like Kill the Robot and Sobriety and Anarchist Struggle started popping in the scene. Zines carried straight edge ideas out of DC into other parts of the country, making it a national, almost religious, movement.

***

From the early to mid 1980s, after the hardcore band Bad Brains paved the way, the local punk scene started to explode. But with more people participating, there was more room for violence, misogyny, and other hateful behavior to seep in. “Nazi punks” formed a white supremacist subculture in the scene, touting shaved heads and Swastikas as an attempt to shock.

Right around the peak of the Nazi punk rise, Mark Andersen moved to DC from Montana to attend grad school at Johns Hopkins and to participate in the punk scene he’d heard so much about from afar. He was immediately confronted by a Nazi group’s graffiti on a pay phone near his house in Adams Morgan. His glorified idea of the DIY, straight edge scene came crashing down.

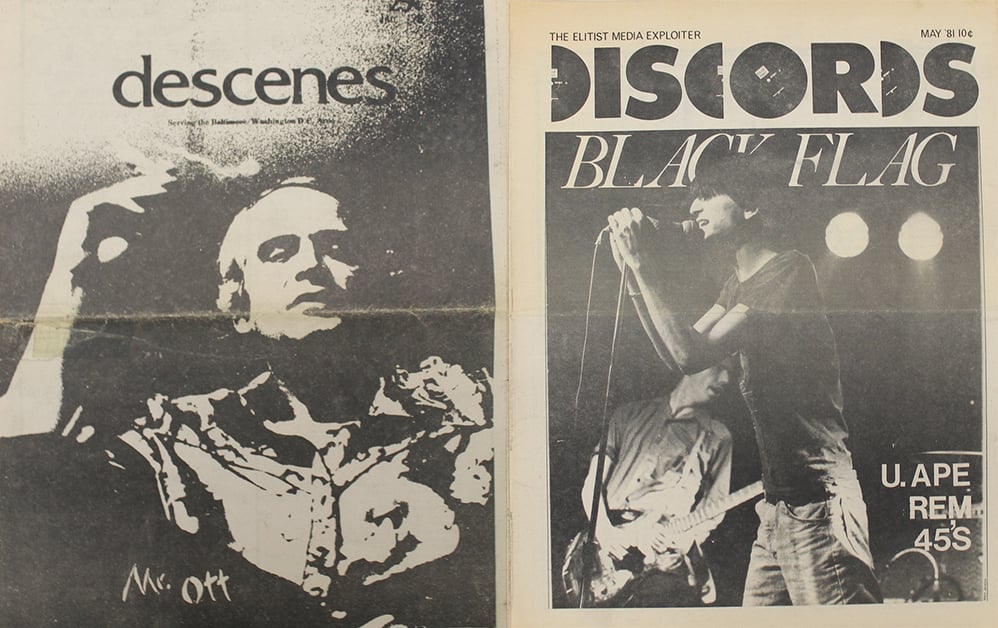

Other people in the scene were similarly disillusioned and started to form a separate movement to counteract the hate. Andersen was able to translate the disillusionment into an activist group called Positive Force which tried to “turn the rhetoric of punk into action” by holding benefit concerts, organizing protests, and encouraging political awareness. These ideals culminated in the summer of 1985 or “Revolution Summer.”

On June 21, 1985, a group of punks planted the flag in Revolution Summer with a “punk percussion protest” against apartheid at the South African Embassy. The band Rites of Spring celebrated the revolution with a show at the 9:30 Club. Dozens of benefit shows, anti-apartheid protests and anti-Reagan rallies followed.

“Revolution Summer meant many different things to many different people,” Andersen wrote in a Washington Post op-ed last year. “But the power of the idea lay in its openness, its sense of possibility and its willingness to challenge individual punks and the world.”

Once again, zines were an integral part of this new movement. “It’s crucial that any sort of counterculture like that find its own voice so that its a direct expression of what it’s about,” Andersen says. A column in a 1985 edition of the zine Hands Up! A Positive Direction Magazine reads “What does ‘Punk’ Mean to You?” Columns like this were an interrogation of the punk culture—an outward challenge to the community to define their beliefs. In conjunction with punk songs, zines were crucial for sparking meaningful discourse.

It’s also important to note the importance of zines on an individual level. “As someone who’s on the outside who feels like a misfit, like a fuck-up, you’re desperate to feel some sense of community, of belonging,” Andersen says. “And anything that can help you get to those other misfits or fuck-ups or seekers, is precious beyond words. “That’s what the zines did.”

***

After Revolution Summer, zines became decidedly political. Along with band interviews and scene reports, they criticized the government and took on social issues and civil rights.

“Battling racism, sexism, and homophobia has been an important part of the punk scene in D.C. for a long time and that does get reflected in many of the fanzines from that era,” says John Davis, the manager of UMD’s zine collection and former member of the late 90s’ post-hardcore band Q and Not U, which was signed to Dischord Records.

In the 1990s, more and more people (mostly teens and young adults) were also publishing personal zines (a.k.a “perzines”) that were confessional in tone. In the straight edge zine Kill the Robot, its author wrote about being bisexual in the punk scene, his sister’s suicide, and later, his rejection of straight edge.

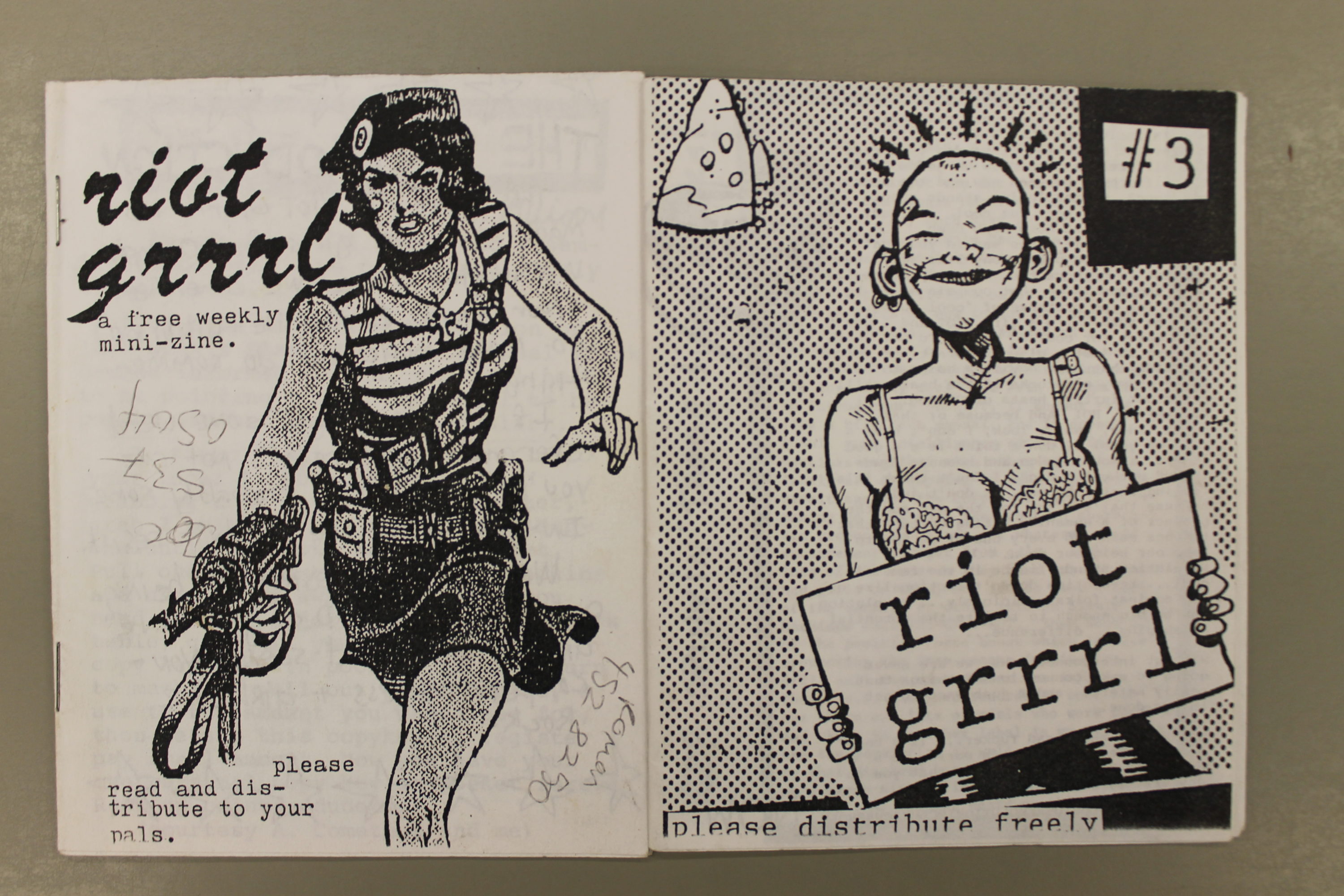

Perhaps the most well-known zine to come out of the ’90s was Riot Grrrl—a “mini zine” that would evolve into a full-blown feminist movement. In 1991, high school and college girls met in the Positive Force house to talk about confronting sexism and staking a claim to the white male dominated scene. Earlier that spring, there were riots in Mount Pleasant following the shooting of a Salvadoran man by a police officer.

Jen Smith, a young activist and musician at the time, is credited with connecting the riots to the Riot Grrrl name. In 1991, she wrote to Allison Wolfe, a member of the all-girl band Bratmobile, “We need to start a girl riot.”

“What she meant was, ‘we need to get politicized,’” says Wolfe, who now lives in LA. Wolfe grew up in Olympia and went to college at the University of Oregon, where she met Molly Neuman. Together, they made the zine Girl Germs and went on to form Bratmobile in DC. “I think the first step for a lot of alternative people is to start a zine, to have a voice,” Wolfe says. “And we did that.” Bikini Kill, a feminist punk band from Olympia and another pioneer of the Riot Grrrl movement, was a zine before it was a band.

Interestingly, Wolfe says the weekly Riot Grrrl zines that she and her friends made by sneaking into Nueman’s father’s PR firm to use its Xerox machine were meant to be disposable. “They weren’t meant to last—they were meant to self destruct,” she says. So it’s telling that they continue to float around 25 years later. Despite their flimsiness, the zines’ cultural salience seems indestructible.

***

Today, DC zine culture has burst wide open. While its roots are still in music, the topics people write about are more diverse than ever. It’s still considered niche but no longer is it tied to one community. And because the Internet has mostly replaced zines’ initial purpose as channels of communication, they’re now more of an expression of art and individuality and less utilitarian.

At Zinefest, there was a table devoted to professional wrestling fandom. Dan Nelson’s zine Hot Tag is an autobiographical account of being a wrestling fan. “There’s this nerdist appeal within the larger appeal of zine culture,” Nelson says. “It’s the nerds of the punk scene all coming together.”

In some ways, that’s what zine culture has always been. Their purpose as a medium has evolved significantly, but they will always contain remnants of their predecessors.